Scott Klass Takes The Davenports Back Home

An interview with Scott Klass of The Davenports leading up to their new album

The band’s longest member talks about his latest album, the evolution of The Davenports’ sound, making beauty out of life’s awkward moments, and more.

The Davenports have been making music for twenty-five years, and while much of its roots remain the same, this Brooklyn-based, indie-pop project’s sound has changed with the years as members have come and gone.

Modern Music Analysis writer Mariel Ferragamo sat down with The Davenports’ Scott Klass, the group’s leading and only constant member, about The Davenports’ latest album, You Could’ve Just Said That.

Described as one of Klass’s most personal works yet, he discusses his familiar influences for YCJST, what it was like making an album from a makeshift home studio, and how he thrives in digging up creative metaphors from universally uncomfortable instances in life.

You Could’ve Just Said That is a delightful album, I’m excited to get into it. What inspired it? Was there a specific moment when you thought, “Oh, this is my idea for my next thing?” Or was it a slow culmination of songs?

More of a slow culmination. I hesitate to say this is my Covid record, but I started this album at the beginning of Covid. We were all on lockdown, and I had a couple of songs lingering in my head. I wanted to start recording them but couldn’t go into a studio. So I forced myself to buy a little gear to try recording them and just see what happened.

It was a totally new process. When I’ve been in studios, I usually let the engineers cope with the details; I never really get into it. But in this case, I had to. I learned it to the degree that I could put down some tracks. It was fun, and they were coming out well, so I started recording. Then I wrote more songs and recorded them, and suddenly, I was like, “I have a whole record here.” So it turned into one that way.

I marveled when I heard that the new album was entirely self-produced. It sounds like it was a learning process for you, being your first time doing this. What was that like?

In some ways, it was great because when you’re working with other people, there are obviously pluses and minuses to everything. Working with other people, you have the joy of collaborating, and that takes the music and expands it to different places. So, the collaboration part was missing.

But the good part was that I didn’t have to interpret this for anybody. In this case, if it’s two o’clock in the morning, I’m like, oh, you know what? I have an idea for a bass part. I could sit down, take out the bass, play it, and do whatever I wanted. There was a freeing aspect where I could do whatever I wanted. I think it made a more personal record.

Going back and listening to your earlier albums, it’s fun to hear how the sound has morphed throughout what are now five EPs. Being the sole constant of this revolving door of people coming in and out and making contributions, do you see a thread connecting where you are now?

A lot of these people who have played in the Davenports through the years, like Dan Miller (They Might Be Giants) — he and I grew up together in upstate New York, and we played in an abandoned high school together. He’s a fantastic musician. So if you take people like him and add all the others, that definitely has fed into the way the music has evolved.

I’ve been a writer for a while. I have my influences, but all the other people who come in and out not only change the sound for the parts they’re playing on but also impact me and the way I think about songs.

The rotating cast of characters that come in and help me is fun because it means you’re not locked into one particular thing. I can start with a song and bring it to people. If I say, “This one is right for strings,” I can bring in my friends Claudia and Eleanor and say, okay, do your thing and put strings on this. And suddenly, they take it to a different place. Or we bring in Jack McLaughlin, who’s played pedal steel. So there’s that benefit of having people coming in and out like that.

Those sounds came through clearly in the album, and overall, there was a strong emphasis on the acoustic, very authentic style. How did you decide which instruments would come together in which songs?

I play many instruments, but the gear I had to record at home was super minimal. I had a couple of acoustic guitars, a bass, and one good microphone for vocals and guitars. I programmed almost all of the drums. There are only three short electric guitar solos on the whole record, and my son played all three of them.

If there’s any bigness to the songs, it comes from the vocals. It’s a very harmony-focused record. That was fun, being able to do almost like a Matthew Sweet thing where I could go in and layer myself six times or something like that.

And because I’m not explaining what to do to anybody else, they could get weird. A lot of them are unconventional harmonies that, in the moment I’m like, oh, I’m just gonna try this instead of what’s expected. I’m like, “okay, this one sucks, I’ll kill that track — but this one’s really good, so I’ll leave that one in.” It made for something more unique.

The emphasis on those harmonies in the album accentuates the meaning of these songs. You don’t hear many pop songs drawing on this theme of calling out real moments in life that are fairly specific — and often uncomfortable — moments we’ve all experienced, like miscommunication. How did you come up with that?

It’s pretty much always the way I’ve written. The songs vary to some degree, but if I go back through all the records, these small stories of discomfort naturally come out to me. Our lives are filled with those moments every single day. As I started to write more of this set, that theme emerged.

I didn’t really pay attention to it as a constant thing, I was just writing what I felt like writing. But when you look at it, you start to see this thread of unspoken, small interactions where stuff is not being said. With all this evasiveness in our day-to-day interactions with friends, family, and anybody really, we’re not perfectly forthright about what’s in our heads at the moment. So it’s a lot about that skirting around our truth and then the discomfort that comes from that.

Then we have the titular song, a significant one in understanding the horizon that the songs weave together. If the album’s theme arose organically, how did you choose “You Could Have Just Said That” to set the tone?

I think it’s emblematic of that idea of how normal it is to not say what is really going on. And that can lead to bigger problems. In that particular song, the mirror to it is “I’m Lying.” It’s the same story told from two different perspectives in two songs. In this case, one partner in the relationship recognizes that the other partner is acting like they’re clearly trying to hide something.

What this person is trying to say is ultimately, “What you did was not a big deal. But because you’re being so evasive, you’re making me more paranoid that there might be something worse going on.” That theme is not in every single song, but it struck me as pervasive enough across the whole body of material that it was the best candidate for a connective theme for the whole thing.

Those everyday, less-than-perfect moments, and calling them out for what they are, that’s powerful. And then there are some, like “Full Length Mirror,” which was born out of a moment with your daughter, right? That was a sweet way to find a poignant metaphor out of something quite simple.

That song came from when she hung a mirror too low. I told her, “You won’t be able to see your face if you leave it there.” It was a random little joke between the two of us, and then, my brain started churning an hour later, like, “Wait a minute, what could that mean?”

Maybe someone could deliberately hang it too low, maybe they feel shame about something they’ve done in the past, so they don’t want to see their face. So this song started with this funny moment with my kid, and then it evolved into another story about being evasive and not facing some bad shit that you might have done.

That theme of discomfort comes through so vividly, but it’s such a pleasing album to listen to that it adds a level to the EP, packaging the message of an unpleasant concept in an approachable way.

Yeah, I’ve done that a lot. I’m not unique in that way; other artists have that ironic distance or whatever you want to call it. But it seems to be the kind of thing that I just felt naturally. I love pop music, and sometimes a song itself can be melancholy, like the last song, “We Know We Want To.” But a lot of times, it’s very pop-y and upbeat, and playing against that can sometimes make it even more poignant.

I did a video that hasn’t come out yet for “We Know We Want To.” This is effectively a love song. It’s got a unique spin because it’s about a polyamorous relationship, but it’s effectively a heartbreak song. But I told the production team that the last thing I wanted was for this video to play literally to the song. I don’t want it to be sappy and show sadness. I want there to be some other visual that takes people to some other place.

It’s almost like trippy psychedelia. There’s a little bit of a Peter Gabriel Sledgehammer, stop-motion animation, hand-cut collage kind of thing. Some people will look at it and wonder, what the hell is this? This is so irrelevant to the song. And then to some people, it might be like, oh, okay. It is impacting me in a different way. It’s that same idea, that juxtaposition of two things.

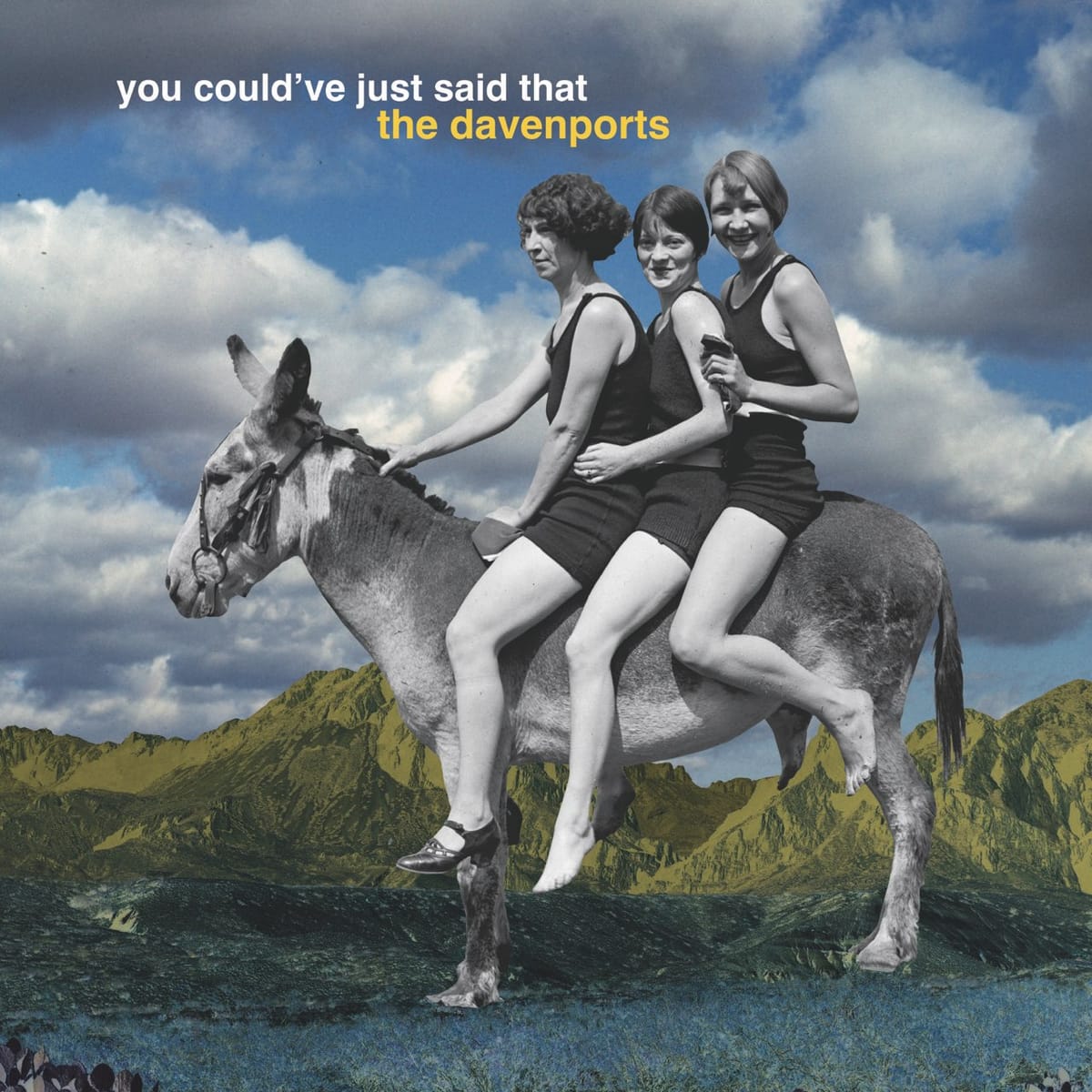

Another parallel I want to talk about is the cover art. This album, and some of your past albums, too, feature this clash of retro-style photos with a modern spin on them, playing with color and layering. Is there an intention with that? What does that signify to you?

There’s been a lot of nostalgia imagery thrown on our stuff. It might be that much of what I’m writing about stems from relationships, starting with family. So that kind of thing has felt right.

Philip Price created the artwork for a couple of the singles leading up to this album and the album cover. He picked up a bit of that same motif; there’s a bit of nostalgia, but then he took it to this very weird, almost surrealist place.

It’s one of those things where some people will look at it and be like, “I don’t get it.” And some people will look at it and be like, “I get it completely.” So I just loved it. I’m trying not to analyze every image or video and see, “Oh, how does this fit?” It’s just how it makes you feel as you’re experiencing it. I saw it, and I thought, “This feels amazing to me.” So that’s how it happened.

That was my experience when I looked at the artwork—whether or not I “got it” wasn’t a factor in enjoying it. I don’t know that any greater point was immediately clear to me, I just loved the vibe it put out.

Yeah, if anything, it’s just fun. There’s so much to see in it. Your brain will go wherever it wants to.

One of my favorite things is when someone takes a song that might be famous and marries it to a movie clip or something like that or a video clip that has absolutely nothing to do with the song.

There’s a Terrence Malik movie, Badlands, from the seventies; someone took that and merged it with the song by this band, Drug Dealer, called Honey. There’s something about the marriage of the footage and song. It’s like, you don’t know why, but it just fits so perfectly. Now, anytime I want to hear that song, I go back and watch that video instead of just listening to it by itself because there’s something more fulfilling about it. I don’t know, it’s weird.

Well, we’ve covered a lot of territory, but is there anything we haven’t discussed that you want listeners to take away from this album?

I don’t think so, to be honest with you. There are rabbit holes to go down, but it’s not necessary to get into them. I think that we captured its essence, which is all you really need.

Dive even deeper with links to stream the full album and a review of You Could’ve Just Said That here.

Comments ()